2016年10月7日接连发生的三件事在罗比·穆克的记忆中尤为突出。

第一次是在下午3:30左右。奥巴马政府发表声明,公开指责俄罗斯入侵民主党全国委员会并策划发布数千封困扰民主党的电子邮件,称这些邮件“意在干涉美国选举进程”在这一天疯狂的新闻周期中,这一极不寻常的公告从未有过机会。

下午4点,《华盛顿邮报》公布了臭名昭著的“进入好莱坞”录像带,在录像带上,当时的候选人唐纳德·特朗普吹嘘自己对女性的性骚扰。“当你是明星时,他们让你做。你可以做任何事。抓住他们的阴部。你可以做任何事。"

不到一小时,又一枚媒体炸弹落下。维基解密公布了另一批电子邮件——从希拉里·克林顿竞选主席约翰·波德斯塔的账户上窃取的50,000封黑客邮件中的前20,000页。

朱厄尔·萨马德/法新社/盖蒂

默克回忆道:“事情非常清楚。”他当时是一名35岁的政治特工,负责克林顿竞选。最终,记者们会翻出华尔街银行付费演讲的旧抄本、关于天主教选民的有争议的评论以及其他证明对克林顿竞选不利的文件。美国情报部门已经将波德斯塔宝藏与俄罗斯军方联系起来。

三年后,随着美国为新的总统选举做准备,穆克和其他专家预计俄罗斯将再次发动袭击。他们将继续使用克格勃官员——包括一名在东德德累斯顿假扮翻译的年轻新兵弗拉基米尔·普京——在冷战期间完善的现代版“阿吉普”(煽动和宣传的混搭)。

大多数情报官员和俄罗斯专家都同意,俄罗斯人的总体意图一直是用联邦调查局局长克里斯托弗·瑞(Christopher Wray)的话说,“让我们振作起来,让我们相互对立,制造分裂和不和,破坏美国人对民主的信心”。或者像理查德·克拉克,美国国务院和国家安全委员会的前成员,一位经验丰富的冷战战士所说的那样:俄罗斯人真正想要的是“美国人民放弃我们的制度”。"

联邦调查局局长克里斯托弗·瑞

网络安全专家约书亚·富兰克林(Joshua Franklin)表示,许多活动已经开始实施更好的网络安全卫生措施——每隔30天左右清除系统中的旧电子邮件和短信,并要求员工在登录时使用双因素身份认证(通过两种设备验证身份),他曾为众多参与制定选举安全标准的政府和私人机构工作,目前正在为许多活动提供咨询。

随着2020年11月越来越近,越来越多的公民、公共政策倡导者、政治家、州和地方选举官员以及国家安全机构竞相支持俄罗斯在2016年选举期间协调的网络恶作剧运动暴露出来的大量安全漏洞。穆勒调查期间,国会向各州拨款3.8亿美元,用于改善选举网络安全。

Mook现在已经扮演了两党的角色。2017年,他与米特罗姆尼(Mitt Romney)2012年总统竞选的前竞选经理共和党人马特罗迪斯(Matt Rhoades)合作,在哈佛大学附属智库建立了捍卫数字民主项目(D3P)。该组织的目标是保护民主国家免受网络和信息攻击。上个月,D3P的一个分支获得了联邦选举委员会的批准,为政治竞选提供免费和低成本的网络安全服务,而不违反竞选金融法。

前联邦调查局网络专家、网络安全公司Agari威胁研究高级主管克莱恩·哈斯尔德(Crane Hassold)表示,既然穆克和他的合作者获得了批准,更多的活动将能够部署银行用来识别欺诈活动的那种年龄模式识别软件,以监控可能的鱼叉式网络钓鱼电子邮件和大数据文件的异常输出。

竞选团队现在采取的预防措施倾向于解决昨天的问题,比如民主党全国委员会的黑客攻击,这最终对2016年的克林顿竞选造成了极大的破坏。情报和安全专家担心的是俄罗斯人在2020年可能会做的事情,这些事情要么在最近两次选举后被忽视,要么突然出现。“我们认识到我们的对手将继续调整和提升他们的游戏,”联邦调查局的瑞在4月份对外交关系委员会说。

为了理解俄罗斯计划如何削弱美国人对美国民主制度的信心,网络安全专家和竞选官员正在2016年和2018年选举的余波中挖掘线索。有很多事情要担心。

宣传战

2016年大选前不久,华盛顿大学研究员凯特·斯塔尔伯德开始研究#BlackLivesMatter运动的在线对话。她和她的团队跟踪了一些最活跃的推特账户,并追踪了他们推特的影响力。

伊芙琳·霍克斯坦/华盛顿邮报/盖蒂

研究人机交互的Starbird首先被这些内容的毒性所震惊——以及辩论变得如此尖酸刻薄和两极化,一些人鼓吹暴力,另一些人使用种族主义语言。随后,就在该小组于2017年10月发表第一篇关于该主题的论文后几周,脸谱网的代表向国会调查人员承认,他们追踪了一家名为俄罗斯互联网研究机构(IRA)的神秘俄罗斯公司的广告销售额,该公司有推动亲克里姆林宫宣传的历史。美国情报机构已经得出结论,俄罗斯付钱给社交媒体巨魔来传播虚假新闻和影响公众舆论。广告聚焦于政治分歧问题,如持枪权、移民和种族歧视。

这个消息让斯塔伯德和她的团队怀疑是否有巨魔参与了她研究过的任何对话。去年11月,当众议院情报委员会公布了推特给他们的与爱尔兰共和军有关的账户清单时,斯塔伯德和她的团队决定去看看他们是否认识任何人。他们被自己的发现震惊了。列表中的几十个账户出现在他们的数据中——有些是转发次数最多的。爱尔兰共和军的账户也伪装成真正的#黑人名人和#黑人名人活动家。

当斯达伯德和她的团队回到2016年的数据时,他们发现爱尔兰共和军的网络巨魔们已经建立了紧密合作的并行操作,允许他们两面讨好。他们采用在线活动人士的角色,渗透社区,模仿其他参与者的情绪,然后,当机会来临时,作为有影响力的人,巧妙地而不是如此巧妙地塑造对话。一些人采用相对温和的人物角色,坚持团队精神,建立一个值得信赖的品牌。其他人则是投掷炸弹者,采用美国政治身份的漫画,煽动不同意见的火焰。“他们的目标是左边的黑人生活事件对话,然后是右边的在线保守激进主义,”她说。

“所以在左翼和支持黑人生活的组织中,你可以有像‘给警察打电话’这样的账户,他们打电话给警察猪,鼓吹对警察的暴力行为,一些爱尔兰共和军巨魔用这种方式说了一些最糟糕的事情,”斯塔伯德说。“然后在右边,他们使用种族绰号,说一些更恶劣的话。在某些情况下,你让他们的巨魔在一边和他们的巨魔争论,只是为了互相说些下流的话。”

乔·雷德尔/盖蒂

2016年,俄罗斯在线人物将为右翼特朗普美言几句,诋毁并试图让人们不要投票给左翼希拉里。2020年,喜达屋预计这些巨魔会加大努力“分化左派”由于候选人争夺注意力的领域非常拥挤,巨魔可能会采用与特定候选人一致的人物角色,渗透到讨论中,然后尽可能利用他们的位置攻击其他民主党候选人(可能得到他们旁边小隔间巨魔创造的其他人物角色的支持),并压制最终的投票。

“你会看到他们经常模仿“抵抗”和其他类型的民主党人物,并开始诋毁其他候选人,”她说。“尤其是一旦民主党选择了一名候选人,他们会诋毁所选的候选人,并说,‘哦,这个人不代表我们。我们不能投票给他们。因此,我不会投票。“

对抗巨魔

这一次,巨魔不再有惊喜的优势。正在努力阻止他们或减少他们的影响。

在越来越大的政治压力下,脸书和推特都发誓要关闭巨魔。在2018年中期选举之前,联邦调查局确认了爱尔兰共和军运营的几十个账户和页面。Facebook立即停用了它们。它还建立了一个“作战室”,实时监控威胁的出现。

科林·斯特朗、肖恩·埃吉特和理查德·萨尔加多致力于打击脸书和推特上的巨魔德鲁·安格雷尔/盖蒂

与此同时,联邦机构已经加大努力帮助选民发现机器人和虚假信息运动。西弗吉尼亚州、爱荷华州、堪萨斯州、俄亥俄州和康涅狄格州的选举官员计划将虚假信息教育纳入他们的选民教育计划。

军方的网络司令部也很活跃。在2018年选举之前,他们发起了一场阻止2016年影响力运动背后的俄罗斯人的运动,警告俄罗斯特工停止努力,并将爱尔兰共和军经营的巨魔农场关闭几天。

但是没有人对未来的挑战抱有任何幻想。今年1月,国家情报局局长丹·科茨(Dan Coats)向参议院情报委员会表示,我们预计俄罗斯将继续“专注于加剧社会和种族紧张局势,破坏对当局的信任,并批评被视为反俄罗斯的政客”。“莫斯科可能会以更有针对性的方式使用额外的影响力工具包——如散布虚假信息、实施黑客和泄露操作或操纵数据——来影响美国的政策、行动和选举。”

联邦调查局的瑞说,俄罗斯人不仅在2018年继续他们的策略,“而且我们已经看到一个迹象,他们正在继续调整他们的模式,其他国家也对这种方法非常感兴趣”。

修辞目标一如既往。克拉克说:“他们希望美国人民认为政治和政治家很糟糕。”。“有僵局,什么也做不了。他们希望我们向内看,看着对方的喉咙。”

助长犬儒主义和分裂的愿望也有助于解释俄罗斯2016年袭击的另一个关键部分——以及为什么我们应该如此担心我们2020年的弱点:俄罗斯渗透我们选举基础设施的努力。

黑进选票

苏珊·格林哈尔不能肯定俄罗斯人在2016年选举日成功侵入了北卡罗来纳州达勒姆县的选民登记系统,并导致了她目睹的大范围混乱。她也不能提供任何证据来证明他们是选民登记名册上奇怪问题的幕后黑手,这些问题在2018年选举当天搅乱了俄亥俄州、宾夕法尼亚州、印第安纳州、佐治亚州和佛罗里达州的工作。

但是,如果有人想战略性地压低投票数,激怒很多人,并在地方层面质疑美国选举的真实性,格林哈尔认为这可能很像她在这两个选举日实时看到的情况。这些事件都没有得到充分调查——有些根本没有。根据穆勒报告,在佛罗里达州,2016年至少有一个县的投票系统遭到黑客攻击(州长和县官员对哪一个保持沉默)。

格林哈尔担心2020年11月可能会发生什么。

格林哈尔是一名前化学商品经纪人,她在21世纪初放弃了金融,并找到了倡导选举安全的新主张。随着全国各县开始转向电子投票和电子选民登记系统,她开始为呼吁纸选票和其他防止故障、黑客和欺诈的保护措施的组织工作。她还开始自愿参加现有的快速反应选举监督小组,以解决选举日可能会干扰宪法保护的投票权的任何问题。2016年,在选举日的早上,她在曼哈顿中城的一个法律办公室里管理着一个巨大的呼叫中心。她被分配到一个负责监督和应对北卡罗来纳问题的小组——几乎在早上6:30投票开始后,电话就开始了。

投票工作人员用来登记选民的笔记本电脑和平板电脑上装载的选民登记名册的电子版本似乎是不正确的——因为许多选民被告知他们已经投票,而他们坚持说他们没有投票。其他投票工作人员发现自己根本无法查找任何数字信息。

马修·哈奇/SOPA图像/光火箭/盖蒂

这些问题如此普遍,以至于仅仅几个小时之内,县选举官员就决定完全放弃电子版的选民名册,以传统的方式行事。这就产生了一系列新的问题:当投票工作人员争着要法律要求的纸质投票卷和纸质表格时,他们排起了长队,脾气暴躁。一个选区的投票暂停了两个小时。与此同时,数十名选民彻底气馁,放弃工作或回家。

格林哈尔说:“这条线花了几个小时才穿过并消散。”。“所以那天它确实对人们的投票能力产生了影响。”

对格林哈尔来说,这似乎很可疑。几周前,美国有线电视新闻网报道称,一家投票系统供应商遭到俄罗斯情报机构的袭击,联邦调查局正在调查此事。她通过她的联系人听说供应商的名字是虚拟现实系统。中午时分,埋在一则新闻故事中,她读到了一句让她不再感冒的话:夏洛特一年前刚刚和虚拟现实系统公司签订了一份合同,使用他们的电子投票系统。格林哈尔联系了国土安全部。

“他们非常感兴趣,”她回忆道。

然而,直到今年6月,DHS在接受《华盛顿邮报》采访时透露,他们最终计划对选举期间使用的笔记本电脑进行法医分析——北卡罗来纳州选举官员直到选举后几个月才提出要求,坚称他们可以自己进行调查。在此期间,穆勒和他的团队提交了详细描述俄罗斯情报人员活动的起诉书,然后发布了他期待已久的报告。他们证实,在2016年选举前的几周,俄罗斯情报人员不仅试图黑进虚拟现实系统,他们还向122名当地选举官员发送了“鱼叉式网络钓鱼”电子邮件,这些官员是公司的客户(换句话说,个性化电子邮件旨在欺骗他们点击链接或打开附件,从而允许黑客渗透账户)。同一个俄罗斯军事单位已经探测了至少21个国家系统,寻找漏洞。

穆勒报告本身指出,2016年8月,俄罗斯军事情报部门成功“在公司网络上安装恶意软件”,该公司是美国一家未透露姓名的选民登记技术供应商。格林哈尔说,该公司被广泛怀疑是虚拟现实系统公司。

虚拟现实系统公司承认,俄罗斯黑客显然试图渗透其投票系统,向员工和客户发送电子邮件网络钓鱼攻击。该公司坚称其员工的电子邮件账户没有被泄露,并立即警告所有客户此次攻击。该公司在一份声明中表示:“没有人向我们表示他们已经打开了邮件。”。该公司表示,它一直与执法部门合作,并加强了网络安全。

与此同时,格林哈尔对选举基础设施脆弱性的担忧日益加剧。事实上,在2018年中期选举期间,她目睹了同样的事情发生。这一次,其他州也报道了一些问题。在俄亥俄州、宾夕法尼亚州、印第安纳州和佛罗里达州,一些选民出现了,被错误地告知他们已经在缺席投票中投票。在格鲁吉亚,一些选民出现在投票站,他们在那里投票多年,发现他们的地址已经改变,不再与身份证上的地址相匹配。其他人得知他们的注册突然消失了。

格林哈尔说,在大多数情况下,技术再次介入。

她还没有准备好给2016年或2018年的选举一份干净的健康法案。她没有被DNI的科茨说服,科茨在1月份告诉国会,美国“没有任何情报报告显示我们国家的选举基础设施有任何可能在2016年或2018年阻止投票、改变计票或破坏计票能力的妥协”。

她的怀疑是否有根据,对俄罗斯人来说可能并不重要。他们的主要目标不是改变结果——而是削弱信心。换句话说:投票是否被操纵并不重要。如果美国公民认为这是被操纵的,那么这次行动是成功的。

那么,我们能做些什么呢?

当然,正在努力加强对选举基础设施的保护。问题在于:美国选举制度由数千名县、市、镇选举官员分散管理,其中许多人小心翼翼地保护自己不受联邦政府的影响。电子投票机制造商已经与地方和州选举官员建立了舒适的旋转门关系。

这有助于解释对一些选举安全倡导者来说似乎无法解释的事情:为所有联邦选举设定新的网络安全标准的立法已经在美国参议院搁置数月。(参议院多数党领袖米奇·麦康奈尔迄今拒绝将其提交投票)。

纽约大学法学院布伦南司法中心选举改革项目主任劳伦斯·诺顿说:“穆勒报告的一部分只是对我们需要如何做好更多准备的一个呼吁,面对对我们选举的明确攻击,我们做得还不够。”。“令人惊讶的是,在修补这些漏洞方面做得很少。”

他指出,这些系统中的许多都有巨大的安全漏洞。诺顿说,早在2016年在达勒姆造成如此多问题的那种电子投票书至少在34个州使用。信息通常在云上,或者由无线组件维护,而这些组件尚未建立联邦安全标准。截至2017年5月,至少有41个州正在使用十多年前的投票系统,运行不再提供服务或安全补丁的软件。

与此同时,至少有11个州继续在一些县和城镇使用无纸投票机——尽管美国国家科学院、参议院和众议院情报委员会以及DHS警告说,他们需要用一个至少有纸质备份的系统来代替无纸投票机。

负责生产和编程投票机以及维护注册数据库的私营供应商——甚至在某些情况下清点选举之夜的回报——不受监管。诺顿说:“我们不知道他们雇佣谁,他们在安全方面有什么样的筛选程序,他们的网络安全最佳实践是什么,谁拥有他们,甚至他们是谁,有多少人。”。

我们不知道的

对许多人来说,俄罗斯人和2020年最令人担忧的事情是,我们不知道接下来会发生什么。

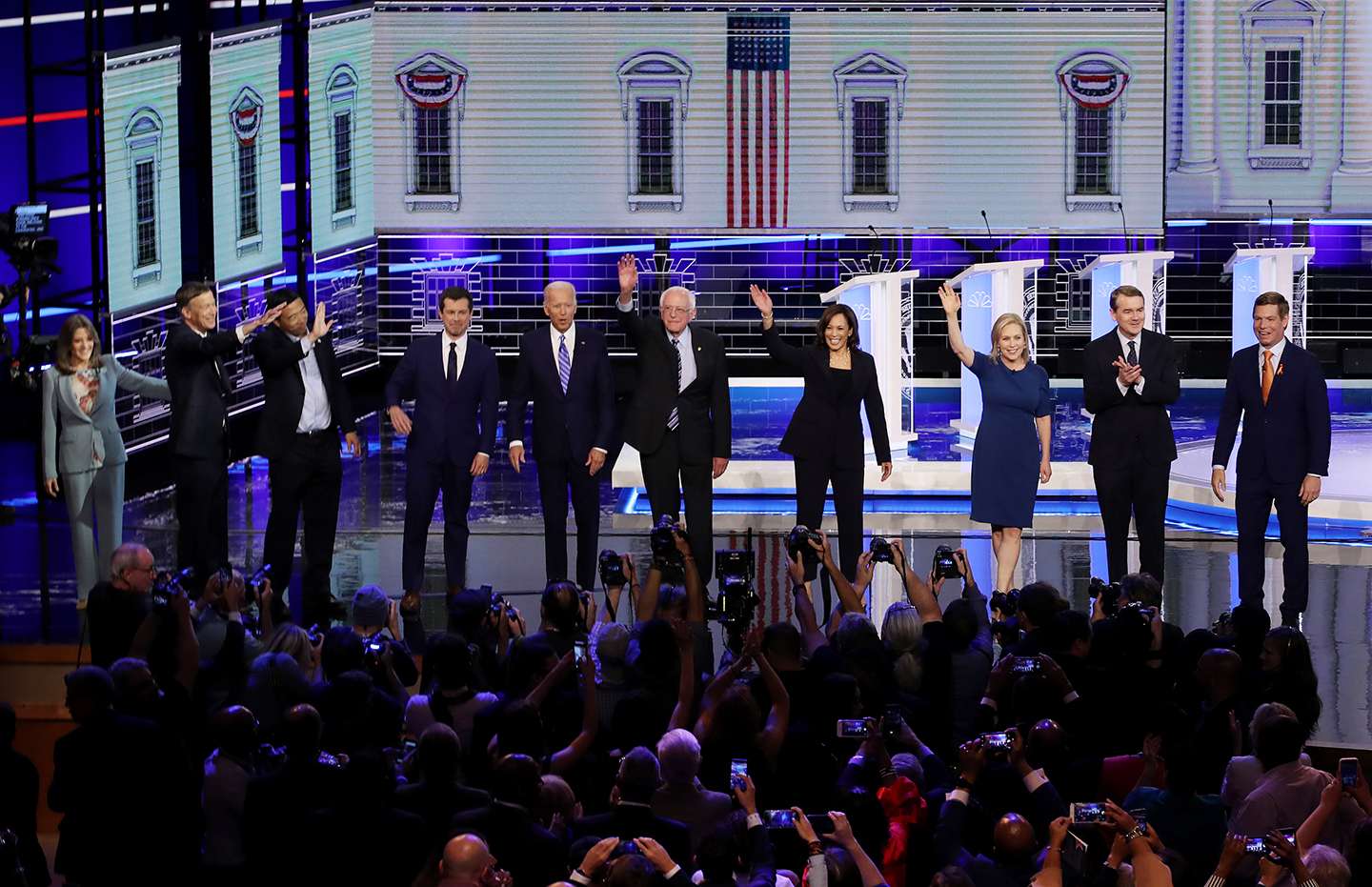

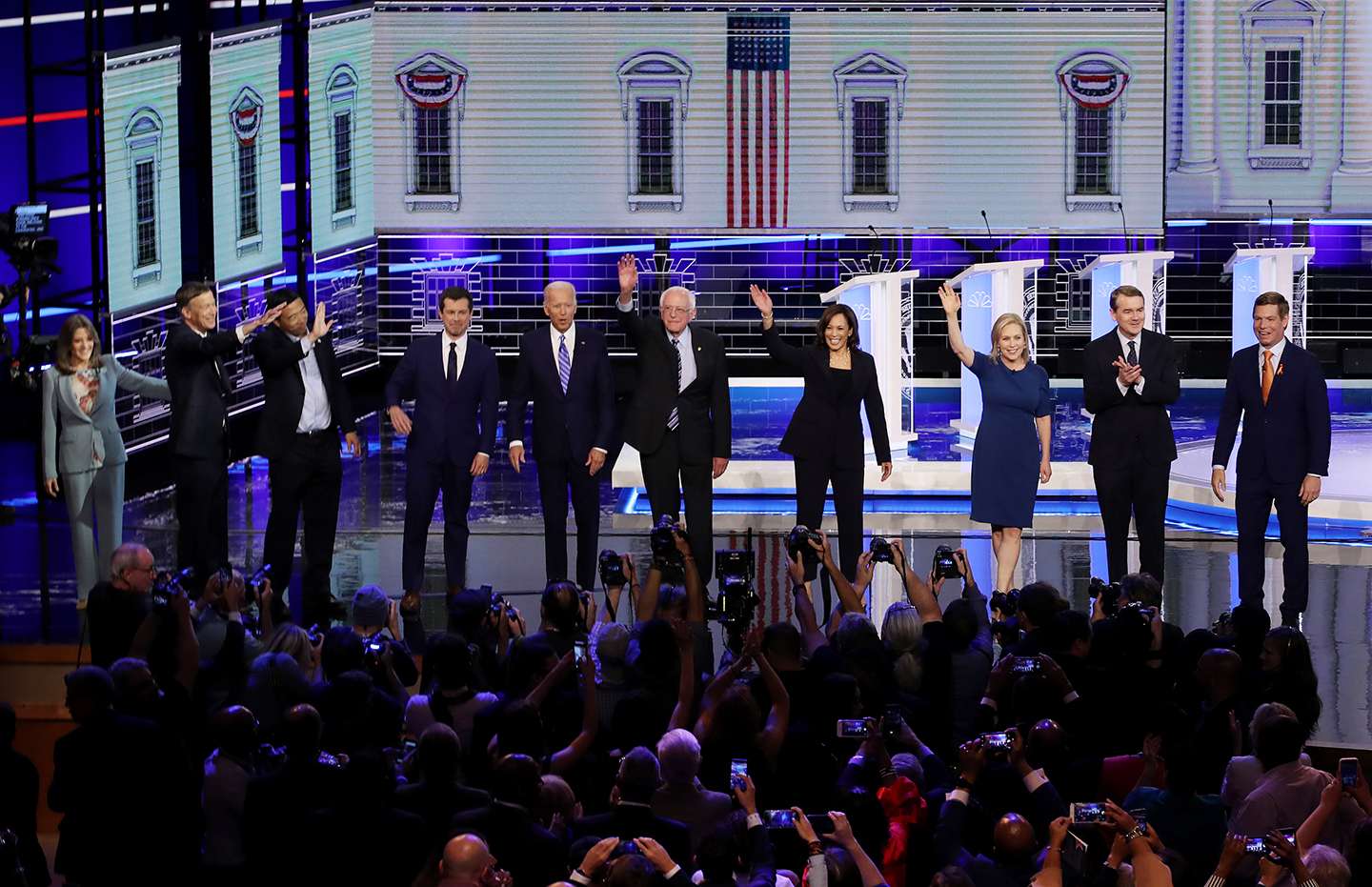

2020年总统竞选的潜在民主党候选人在辩论中。德鲁·安格雷尔/盖蒂

“我担心的是,我们只是在考虑防止2016年的重演,”罗伯·克纳克说,他是国家安全委员会网络安全政策的前主任,也是理查德·克拉克关于网络安全的新书的合著者。

他补充道:“网络冲突的本质是,当你封锁一条道路时,攻击者不会放弃回家...俄罗斯人将寻找其他方式来影响选举,或者这次直接干预投票。”

情报官员已经发现了一种相对较新的武器。科茨在国会作证时警告说,俄罗斯人可能会试图用“深刻的假货”来制造混乱,这些假货是描述从未发生过的事情的篡改视频。软件现在已经广泛可用,可以很容易地把一个人的脸贴在另一个人的身上。一个令人不寒而栗的预兆出现在5月份,当时众议院议长南希·佩洛西含糊不清的低技术篡改视频在脸书上获得了数百万的浏览量。

众议院情报委员会主席亚当·希夫去年春天说:“最严重的升级可能是引入了一个严重的假货——一个候选人说了一些他们从未说过的话的视频。”。“如果你回顾米特·罗姆尼关于47%的支持率的录像带有多有影响力,你可以想象一盘更具煽动性的录像带会如何改变选举。这可能是我们正在走向的未来。”

克拉克最担心的是,俄罗斯人将渗透到关键摇摆州的选民名单中,制造混乱,旨在从战略上压制投票,从而对选举结果的合法性提出更多质疑。

最后,我们对抗这些努力的最有力的工具与技术没有什么关系。尽管铁杆克林顿支持者继续认为2016年黑客攻击的规模是对我们民主的前所未有的攻击,但许多经验丰富的冷战分子更喜欢把它放在一个更大的背景下。一些人认为,按照历史标准,我们好战的斯拉夫敌人使用了更具侵略性的手段战术。在那里毕竟,那是一个他们控制工会并能动员成千上万人代表他们进行鼓动的时代。

英国作家兼安全政策专家爱德华·卢卡斯说:“这些都不起作用,因为它们很好。”他的许多著作包括新冷战:普京的俄罗斯 和对西方的威胁。“这一切都是因为我们软弱。”

Russia Is Using Cold War Strategy to Undermine the Faith of Americans in the 2020 Election—Will It Work?

Three events occurring in rapid succession on October 7, 2016, stand out in Robby Mook's memory.

The first came at about 3:30 pm. The Obama Administration issued a statement that publicly blamed Russia for hacking the Democratic National Committee and orchestrating the release of the thousands of emails roiling the Democratic Party, which, it said, were "intended to interfere with the US election process." In the day's crazy news cycle, that highly-unusual announcement never had a chance.

At 4 pm, The Washington Post unveiled the infamous Access Hollywood Tape, on which then-candidate Donald Trump was recorded boasting about his own sexual harassment of women. "When you're a star, they let you do it. You can do anything. Grab 'em by the pussy. You can do anything."

Within the hour, yet another media bomb dropped. Wikileaks released another trove of emails—the first 20,000 pages of 50,000 hacked emails stolen from the account of Hillary Clinton's Campaign Chairman John Podesta.

JEWEL SAMAD/AFP/GETTY

"It was so clear what was happening," recalls Mook, who at the time was a 35-year-old political operative running the Clinton campaign. In time, reporters would dig out old transcripts of paid speeches to Wall Street banks, controversial comments about Catholic voters and other documents that turned out to be damaging to the Clinton campaign. U.S. intelligence has since linked the Podesta trove to the Russian military.

Three years later, as the U.S. gears up for a new presidential election, Mook and other experts expect the Russians to strike again. They'll continue using their modern version of "agitprop" (a mashup of agitation and propaganda) that KGB officers—including a young recruit posing as a translator in Dresden, East Germany named Vladimir Putin—perfected during the Cold War.

The overall intent of the Russians, most intelligence officials and Russia experts agree, has always been to "to spin us up, pit us against each other, sow divisiveness and discord, undermine Americans' faith in democracy," in the words of FBI Director Christopher Wray. Or as Richard Clarke, a former member of the State Department and the National Security Council and a seasoned Cold Warrior, puts it: what the Russians really want is for "the American people to give up on our system."

Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Christopher Wray.CHIP SOMODEVILLA/GETTY

Many campaigns have already begun practicing better cyber-security hygiene—purging their systems of old emails and text messages every 30 days or so and requiring workers to use two-factor authentication when they log in (verifying their identity from two devices), says Joshua Franklin, a cybersecurity expert who has worked for a wide array of government and private institutions involved in coming up with election security standards, and is consulting for a number of campaigns.

As November 2020 gets closer, a growing army of private citizens, public policy advocates, politicians, state and local election officials and national security agencies are racing to shore up the vast patchwork of security vulnerabilities laid bare by Russia's coordinated campaign of internet mischief during the 2016 election. During the Mueller investigation, Congress gave $380 million to the states to improve their election cyber-security.

Mook has now taken a bipartisan role. In 2017, he partnered with Republican Matt Rhoades, former campaign manager for Mitt Romney's 2012 presidential campaign, to establish the Defending Digital Democracy Project (D3P), at a Harvard University-affiliated think tank. The aim of the organization is to protect democracies from cyber and information attacks. Last month, a D3P spinoff won approval from the Federal Election Committee, to provide free and low-cost cybersecurity services to political campaigns without violating campaign finance laws.

Now that Mook and his collaborators have won that approval, more campaigns will be able to deploy cutting age pattern recognition software of the type used by banks to spot fraudulent activity to monitor for likely spear-phishing emails and the unusual export of large datafiles, says Crane Hassold, a former FBI cyber expert and senior director of threat research at the cybersecurity firm Agari.

The precautions the campaigns are taking now tend to address yesterday's problems, such as the DNC hack that was ultimately so damaging to the Clinton campaign in 2016. The worry of intelligence and security experts is what the Russians are likely to do in 2020 that somehow was either overlooked in the aftermath of the last two elections or comes out of the blue. "We recognize that our adversaries are going to keep adapting and upping their game," the FBI's Wray said to the Council on Foreign Relations in April.

To understand how Russia plans to undermine Americans' faith in the U.S. democratic system, cyber-security experts and campaign officials are digging through the aftermath of the elections of 2016 and 2018 for clues. There's a lot to worry about.

The Propaganda War

Shortly before the 2016 election, University of Washington researcher Kate Starbird began studying the online conversations of the #BlackLivesMatter movement. She and her team followed some of the most active Twitter accounts and tracked the influence of their tweets.

EVELYN HOCKSTEIN/THE WASHINGTON POST/GETTY

Starbird, who studies human-computer interaction, was primarily struck by how toxic much of the content was—and how vitriolic and polarized the debate had become, with some advocating violence and others using racist language. Then, just a few weeks after the team published its first paper on the topic in October 2017, representatives of Facebook admitted to congressional investigators that they had traced ad sales totaling more than $100,000 to a shadowy Russian company known as Russia's Internet Research Agency (IRA), with a history of pushing pro-Kremlin propaganda. The US Intelligence community had already concluded that Russia paid social media trolls to spread fake news and influence public opinion. The ads had focused on politically divisive issues such as gun rights, immigration, and racial discrimination.

The news got Starbird and her team wondering if any of the trolls engaged in any of the conversations she had studied. In November, when the House Intelligence Committee released a list of accounts given them by Twitter associated with IRA, Starbird and her team decided to take a look and see if they recognized anyone. They were stunned by what they discovered. Dozens of the accounts in the list appeared in their data—some among the most retweeted. IRA accounts were also masquerading as genuine #BlackLivesMatter and #BlueLivesMatter activists.

When Starbird and her team went back into their data from 2016, they found that IRA internet trolls had set up parallel operations that worked in close concert, allowing them to play both sides of the fence. They adopted the personas of online activists, infiltrating communities, and mimicking the sentiments of other participants, and then, when the opportunity struck, acting as influencers, subtly and not so subtly shaping the conversations. Some adopted relatively mild personas, sticking with the pack, building a trusted brand. Others were bomb throwers, adopting caricatures of US political identities and fanning the flames of dissent. "They targeted both Black Lives Matter conversations on the left, and then online conservative activism on the right," she says.

"So on the left and in the pro Black Lives Matter group, you could have accounts like 'bleep the police' who are calling police pigs and advocating for violence against police, and some of the IRA trolls are saying some of the worst things in that kind of vein," Starbird says. "And then on the right they are using racial epithets and saying some of the nastier things. In some cases, you have their troll on one side arguing with their troll on the other side just to say nasty things to each other."

JOE RAEDLE/GETTY

In 2016, Russian online personas would put in a good word for Trump on the right and denigrate and try to get people not to vote for Hillary on the left. In 2020, Starbird expects these same trolls to ramp up their efforts to "divide the left." With a crowded field of candidates vying for attention, trolls may adopt personas aligned with specific candidates, infiltrate discussions and then, whenever possible, use their positions to attack other Democratic candidates (likely supported by other personas created by the trolls in the cubicles next to them) and depress the eventual vote.

"You'll see them mimicking regularly the "resist" and other sorts of Democratic personas, and start denigrating the other candidates," she says. "And especially once the Democrats choose a candidate, they'll denigrate the chosen candidate, and say, 'Oh this person doesn't represent us. We can't vote for them. Therefore, I'm not going to vote'."

Countering the Trolls

This time, the trolls no longer have the advantage of surprise. Efforts are underway to block them or reduce their influence.

Under mounting political pressure, both Facebook and Twitter have vowed to shut down the trolls. Before the 2018 mid-term election, the FBI identified dozens of accounts and pages operated by the IRA. Facebook promptly inactivated them. It also set up a "war room" to monitor threats as they emerged in real time.

Colin Stretch, Sean Edgett, and Richard Salgado working to combat trolls on Facebook and TwitterDREW ANGERER/GETTY

Federal agencies, meanwhile, have ramped up efforts to help voters spot bots and disinformation campaigns. Election officials in West Virginia, Iowa, Kansas, Ohio and Connecticut plan to include disinformation education in their voter education programs.

The military's Cyber Command has also been active. Before the 2018 election, they launched a campaign to deter the Russians behind the 2016 influence campaign, warning Russian operatives to cease their efforts and knocking a troll farm run by the IRA offline for several days.

But no one is under any illusions about the challenges that lie ahead. We expect Russia to continue "to focus on aggravating social and racial tensions, undermining trust in authorities, and criticizing perceived anti-Russia politicians," Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats told the Senate Intelligence Committee in January. "Moscow may employ additional influence toolkits—such as spreading disinformation, conducting hack-and-leak operations, or manipulating data—in a more targeted fashion to influence US policy, actions, and elections."

Not only did the Russians continue their tactics through 2018, says the FBI's Wray, "but we've seen an indication that they're continuing to adapt their model, and that other countries are taking a very interested eye in that approach".

The rhetorical goal remains the same as it has always been. "They want the American people to think that politics and politicians are awful," Clarke says. "That there's gridlock, nothing gets done. They want us to be inward-looking, at each other's throats."

The desire to promote cynicism and division also helps to explain another key part of the Russia's 2016 attacks—and why we should be so worried about our 2020 vulnerabilities: Russian efforts to penetrate our election infrastructure.

Hack the Vote

Susan Greenhalgh can't say for sure the Russians successfully hacked into the voter registration system of Durham County, in the swing state of North Carolina back on election day 2016 and caused the widespread chaos she witnessed unfold. Nor can she offer up any proof they were behind the curious problems with voter registration rolls that gummed up the works in Ohio, Pennsylvania, Indiana, Georgia and Florida on election day 2018.

But if somebody wanted to strategically depress vote counts, piss off lots of people, and cast the veracity of U.S. elections into question on the local level, it seems to Greenhalgh it would probably look a lot like what she watched unfold in real time on both those election days. None of those incidents have yet been fully investigated—some of them not at all. In Florida, according to the Mueller report, a voting system in at least one county was hacked in 2016 (the governor and county officials are keeping mum about which one).

Greenhalgh worries what might be in store for November 2020.

Greenhalgh, a former chemical commodities broker, abandoned finance in the early 2000s and found her new calling advocating for election security. As counties around the nation began moving to electronic voting and electronic voter registration systems, she began working for organizations calling for paper ballots and other protections against malfunctions, hacking and fraud. She also began volunteering for rapid response election monitoring groups on hand to solve any issues on election day that might interfere with the constitutionally protected right to vote. In 2016, she manned a vast call center in a law office in midtown Manhattan on the morning of election day. She had been assigned to a group tasked with monitoring and responding to problems in North Carolina – and the calls began almost as soon as the polls opened at 6:30 am.

The electronic version of the voter registration rolls, loaded onto the laptops and tablets that poll workers used to check in voters, appeared to be incorrect – as scores of voters were told they had already voted, when they insisted they had not. Other poll workers found themselves unable to look up any digital information at all.

MATTHEW HATCHER/SOPA IMAGES/LIGHTROCKET/GETTY

The problems were so widespread that within just a few hours county election officials had decided to abandon the electronic version of the registration rolls altogether and do things the old-fashioned way. Which created a new series of problems: as poll workers scrambled for paper versions of the voting rolls and paper forms required by law, long lines formed and tempers boiled. Voting was halted for two hours in one precinct. In the meantime, scores of voters gave up and went back to work or went home, thoroughly discouraged.

"It took hours for the line to work through and dissipate," Greenhalgh says. "So it really did have an impact on people's ability to vote that day."

To Greenhalgh it seemed suspicious. A couple weeks earlier, CNN had reported that a voting system vendor had been attacked by Russian intelligence and the FBI was investigating. She'd heard through her contacts that the name of the vendor was VR Systems. Then around midday, buried in a news story, she read a sentence that stopped her cold: Charlotte had signed a contract just a year before with VR Systems to use their electronic poll book systems. Greenhalgh reached out to the Department of Homeland Security.

"They were very interested," she recalls.

Nevertheless, it wasn't until this June that the DHS revealed in an interview with The Washington Post they finally planned to conduct a forensic analysis of the laptops used during the election—a request North Carolina elections officials did not make until months after the election, insisting they could carry out an investigation on their own. In the interim, Mueller and his team filed indictments detailing the activities of Russian intelligence operatives, and then issued his long-awaited report. They confirmed that in the weeks before the 2016 elections, Russian intelligence agents not only attempted to hack VR Systems, they also sent "spear-phishing" emails to 122 local elections officials who were the firm's customers (personalized emails, in other words, designed to trick them into clicking on links or opening attachments that would allow hackers to penetrate accounts). And that the same Russian military unit had probed at least 21 state systems, looking for vulnerabilities.

The Mueller Report itself noted that in August 2016 Russian military intelligence had managed "to install malware on the company network" of one unnamed voter registration technology vendor in the United States. That company is widely suspected to be VR Systems, Greenhalgh says.

VR Systems has acknowledged that Russian hackers, in an apparent attempt to penetrate its voting systems, sent email phishing attacks to employees and customers. It insists that none of its employees' email accounts were compromised and that it promptly warned all its customers of the attack. "No one indicated to us that they had opened the email," the company said in a statement. The company says it has cooperated all along with law enforcement and has tightened its cyber-security.

In the meantime, Greenhalgh's concern over the vulnerabilities of the election infrastructure have only grown. In fact, during the 2018 mid-term elections, she watched the same thing happen. This time, problems were reported in other states, too. In Ohio, Pennsylvania, Indiana and Florida, some voters showed up and were told, incorrectly, that they had already voted on absentee ballots. In Georgia, some voters showed up at the polling stations where they had been voting for years to find their addresses had been changed and no longer matched those on their IDs. Others learned that their registrations had suddenly disappeared.

In most of these cases, Greenhalgh says, technology was once again involved.

She's not ready to give either the 2016 or 2018 elections a clean bill of health. She is not persuaded by DNI's Coats, who told Congress in January that the US "does not have any intelligence reporting to indicate any compromise of our nation's election infrastructure that would have prevented voting, changed vote counts, or disrupted the ability to tally votes" in either 2016 or 2018.

Whether her suspicions are warranted or not, it probably doesn't matter much to the Russians. Their primary goal isn't to change the outcome—it's to undermine confidence. In other words: It doesn't matter if the vote was rigged. The operation is successful if U.S. citizens just think it was rigged.

So, What Can Be Done?

Sure, efforts are underway to shore up protection of the election infrastructure. The trouble is this: the U.S. elections system is spread out and administered by thousands of individual county, city and town election officials – many of whom jealously guard their autonomy from the federal government. Electronic voting machine manufacturers have cultivated cozy, revolving door relationships with local and state election officials.

This helps explain what to some election security advocates seems inexplicable: Legislation that would set new cybersecurity standards for all federal elections has been stalled in the U.S. Senate for months. (Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has so far refused to bring it up for a vote).

"Part of the Mueller Report was just a cri de coeur about how we need to be more prepared and we haven't done enough in the face of a clear attack on our elections," Lawrence D. Norden, Director of the Election Reform Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law says. "And it is amazing how little has been done to patch up some of these vulnerabilities."

Many of these systems, he notes, have gaping security holes. Electronic poll books of the type that caused so many problems in Durham back in 2016 are used in at least 34 states, Norden says. Often the information is on the cloud, or maintained with wireless components for which no federal security standards have been established. As of May 2017, at least 41 states were using voting systems that are more than a decade old, running software no longer serviced or provided security patches.

At least 11 states, meanwhile, continue to use paperless voting machines in at least some counties and towns - despite warnings from the National Academy of Science, the Senate and House Intelligence Committees and the DHS that they need to replace them with a system that at the very least has paper backups.

The private vendors in charge of producing and programming voting machines and maintaining registration databases—and even in some cases tallying election night returns—are not regulated. "We don't know basic things like who they employ, what kind of screening process they have around security, what their cybersecurity best practices are, who owns them, even who they are, how many there are," Norden says.

What We Don't Know

To many the most alarming thing about the Russians and 2020 is that we don't know what's coming.

Prospective Democratic candidates for the 2020 Presidential Election campaign during a debate.DREW ANGERER/GETTY

"What I'm worried about is that we're only thinking about preventing a repeat of 2016," says Rob Knake, a former director of cybersecurity policy at the National Security Council, and the coauthor of a new book with Richard Clarke on cyber security.

He adds: "It's the nature of cyber conflict that when you close off one avenue, the attackers don't give up and go home ... the Russians will be looking at alternative ways to influence the election, or directly interfere in voting this time."

Intelligence officials have already identified one relatively new weapon. In his testimony before Congress, Coats warned that the Russians might try to sow chaos with "deep fakes"—doctored videos that depict things that never happened. Software is now widely available that makes it easy to paste a person's face on another person's body. A chilling foreshadowing came in May when a low-tech doctored video of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi slurring picked up millions of views on Facebook.

"The most severe escalation might be the introduction of a deep fake—a video of one of the candidates saying something they never said," House Intelligence Chairman Adam Schiff said last spring. "If you look back at how impactful the Mitt Romney videotape about the 47 percent was, you could imagine how a videotape that is more incendiary could be election-altering. This may be the future we are heading into."

Clarke's biggest concern is that the Russians will penetrate voter rolls in key swing states and create chaos aimed at strategically depressing the vote enough to raise more questions about the legitimacy of the election outcome.

In the end, the most powerful tool we have to combat the efforts has little to do with technology. While die-hard Clinton loyalists continue to maintain that the scale of the 2016 hacks constituted an unprecedented attack on our democracy, many seasoned Cold Warriors prefer to place it in a larger context. By historical standards, some argue, our bellicose Slavic foes have employed far more aggressive tactics.There was a time, after all, when they controlled unions and could mobilize thousands to agitate on their behalf.

"None of this works because they're good," says Edward Lucas, a British writer and security policy expert, whose many books include The New Cold War: Putin's Russia and the Threat to the West. "It all works because we're weak."